The issues of executive pressure related to data breach prevention, detection, and notifications are often addressed in media, HHS/OCR audits, and class action lawsuits. However, there also are important challenges to hospital leadership in early response or containment of data breach activity.

The push to improve data breach defense is no longer simply directed at a hospital’s IT organizations but at executive leadership and the board of directors. Current and evolving federal legislation wants hospital executives to ensure that data breach prevention measures are in place. The Senate “Health Care Cybersecurity and Resiliency Act of 2024” attempts to reinforce prevention best practices (often articulated as the implementation of multi-factor authentication (MFA), patch management, data encryption, and employee phishing awareness training). Timeliness of data breach disclosures to HHS and other federal and state agencies has also been increasingly pursued and supported by OCR fines and audits. Class action lawsuits against hospitals have included accusations of failure of prevention measures and failure of timely notifications, as well failure to monitor systems with some claims citing detection times of weeks, months, and even 17 months by different hospitals.

However, executive responsibility goes beyond the aforementioned measures and needs to focus on the response phase of a data breach. Normally, this phase is simply interpreted as executives needing to ensure that the hospital creates an incident response (IR) plan, execute tabletop exercises, and have a team in place to implement the plan. Yet, within the dimensions of data breach attacks, it’s important for executive management to understand the time-critical and tactical phases of IR, known as containment.

Containment is often associated with two different objectives:

- “Stop the bleeding” refers to stopping the loss, or exfiltration, of sensitive data (often patient or ePHI data for hospitals) for systems that are already breached.

- “Stop the spread of the bleeding” refers to stopping the spread of data breach activity to systems, hospitals, and clinics in your organization that have not yet been breached.

Timeliness is a key consideration in containment. Faster implementation of containment could result in:

- Fewer patients being impacted by loss of ePHI data

- Less impact on hospital operations

- Smaller financial impacts to hospitals

- Less exposure to regulatory actions and class action lawsuits

Two Containment Approaches

There are two approaches to data breach containment although the industry often defaults to using one. It is essential for hospital business and clinical executives to understand the types of containment and they may need to be actively involved in containment decisions.

- Isolation containment is the common approach used in the industry and involves the disconnection (logically or physically) of systems, mostly servers, from access by threat actors.

- IP address blocking, which is considered surgical containment, is a narrower form of containment.

Both approaches can have a role in your organization and could be implemented on different systems at different times during the incident response life cycle.

Isolation-based Containment

Isolation containment is, to some degree, the industry-standard approach to data breaches. IT experts appropriately argue that it will stop beach activity on a given server dead in its tracks because the server is offline. Being offline means that threat actors can no longer continue to access and steal ePHI patient data.

Since isolation means disconnecting systems however, it also means operational disruption for doctors, nurses, administrative staff and partners. Indeed, the larger industry issue relating to the Change Health Care breach was a problem of systems being disconnected from different organizations in the healthcare ecosystem.

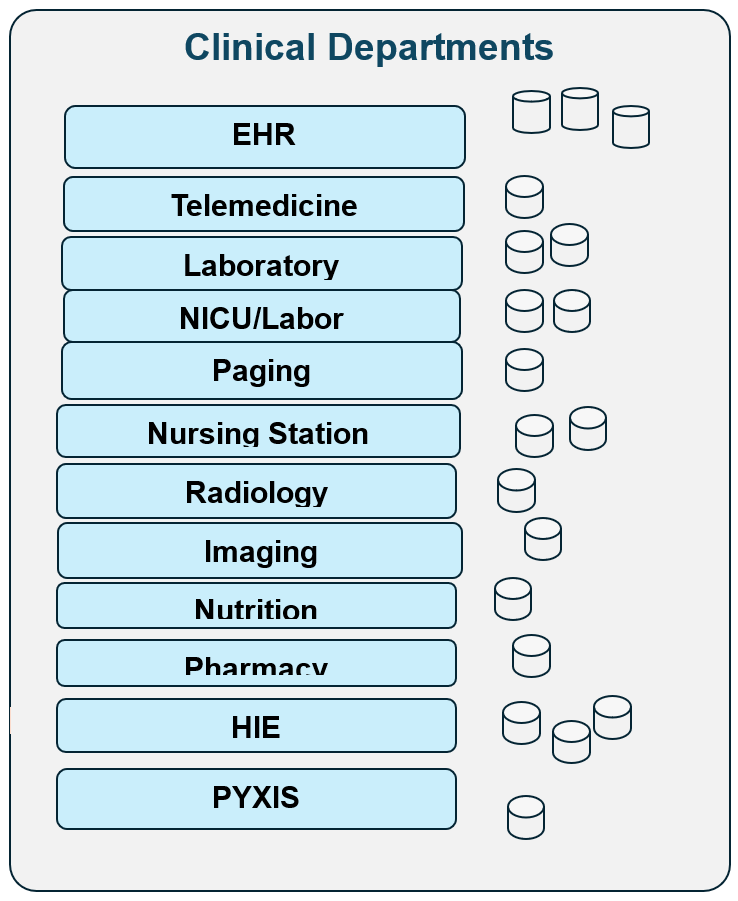

Has your organization established a plan to guide isolation practices for different systems or categories of systems? For example, of the different systems in your hospital, which do you want isolated and for how long when a data breach occurs?

Good definitions and articulations of delegated authority to IT staff or outside Incident Response Firms can be a responsible dimension of executive leadership. However, the advanced planning of systems to isolate may not be sufficient for many reasons:

- Out-of-date plans: In many hospitals, new systems are frequently introduced and integrated.

- Shadow IT: Many hospital systems may be implemented by non-IT departments and may not even be part of any IR plan.

- Legacy Systems: These are often old and fragile. It can be difficult and problematic to install software agents to detect breaches and to implement isolation.

- Real-world impacts: Approximately 24 hours after a breach has occurred and isolation implemented, hospital executives may start to more deeply understand the impacts of isolation including unintended consequences such as

- Nursing stations impacted

- NICU impacts

- Imaging system impacted

- Possible ER diversions needed

At this time, real-time decisions regarding isolation may be needed.

However, hospital boards need to understand how decision-making is defined:

- Are decisions delegated (or abdicated) to hospital IT staff or outside Incidence Response vendors?

- Do IT staff consult with hospital COOs and clinical staff before IT makes a final decision?

- Do you have a policy whereby hospital business and clinical staff make the final decision about which systems to disconnect – with input from IT experts?

Decision-making by business or clinical executives is not easy and can be very stressful. There are several considerations, including:

- How to be responsible for patient safety and hospital operations.

- How to prevent threat actors from directly impacting operations (for example, via encryption).

- How to avoid legal and financial liability relating to regulatory actions or class action lawsuits.

- How to avoid legal responsibility for operational disruption (caused by isolation) to hospital systems and to partners.

In the end, the difficult legal balance (known as “choice of evils”) needs to be addressed from an executive and not from an IT perspective.

Surgical Containment

This is a narrow type of containment that can block communication (and potentially block ePHI theft) by threat actors. It can optionally be used in situations where isolation is not appropriate.

Benefits of using surgical containment include:

- It does not isolate or disconnect the entire server. The server continues to function except for access by threat actors using a given IP address

- It can be implemented quickly at the firewall level.

- It can protect legacy systems since no software agents need to be installed on the fragile legacy system.

- It can stop the bleeding (now) and stop the spread of threat actor attacks against future systems, hospitals, and clinics.

Possible downsides of using surgical containment may include:

- It does not have the certainty of stopping all data breach leakage for a given server. Threat actors may use or start to use a range of IP addresses to steal data over time.

- Threat actors may try and steal data in direct ways (e.g., via Dropbox, email, Wi-Fi systems, or others).

When to Use Surgical Vs. Isolation-based Containment Measures

Executives should consider the following when making decisions related to containment measures:

- Phased Concept: For systems experiencing data breach activity, use Isolation-based containment. For those not yet breached, use surgical containment rather than disconnecting all systems.

- Evolving Concept: Initial IR planning may indicate the use of isolation for selected systems for up to 2 weeks. But 24 hours later, there may be unanticipated impacts. An option would be to stop the isolation and bring some of the servers back online but with surgical containment in place – understanding that surgical containment is not bulletproof but is also not as disruptive as isolation.

Conclusion

Hospital leadership, boards of directors, and trustees need to focus on the protection of patient data from data breaches and to protect hospitals from regulatory (HIPAA) actions and class action lawsuits. Focusing on prevention measures, early data breach detection, and timely disclosures are often discussed in media, courtrooms and hearings. Hospital trustees should also focus on the containment phase of incident response. Policies should be articulated about the leadership and decision-making role of the non-IT staff relating to the use of isolation-based containment, which can directly affect the operations of crucial systems in hospitals and clinics.

Celerium offers a no-cost data breach defense program for hospitals that can facilitate surgical containment and help with early detection of possible data breach activity. Visit Celerium.com to learn more.

About Celerium

Celerium engineers cyber defense solutions to help organizations in the fight against cyberattacks, including data breaches. The company offers a no-cost data breach defense program for hospitals that leverages the Compromise Defender® solution to facilitate early detection of potential data breach activity. To learn more, visit Celerium.com.